Once you get comfortable with the various types of investments, you’re ready for basic principles. Here’s what you need to know before entering the jungle.

Buy low, sell high

One time I toured a scrap yard. The owner kept complaining about the economy but all around me were mounds of scrap. So I finally asked, “If the economy is so bad, why do you have so much inventory?” He said, “It’s an old Jewish lullaby, buy low and sell high. And right now, prices are low.”

Buying stocks is like buying anything else—you want to get a good deal. And if a stock’s price gets so high that not even you would buy it, maybe it’s time to run. Sure you can’t time the market, but you can still buy and sell based on price.

Avoid overpaying by submitting a price along with your buy order. It may take time but you’ll usually get a better deal. Same goes for selling. Most of us forget to sell on overvalue and wind up kicking ourselves after the crash. Avoid this by using a priced sell order that executes when the stock hits a certain peak.

Holding cash

Everyone is usually fully invested, leaving no room in their portfolios for cash. But then how do you capitalize on a good buy?

We figure because cash doesn’t grow—having too much of it means we’re falling behind. That’s total baloney. Cash is the result of selling high and you’ll use it later to buy something better at a good price (maybe tomorrow, maybe next week, maybe in six months). Always keep cash on hand to capitalize on good deals (like during a market correction or crash).

Mutual funds

Ever wonder why there are so many mutual funds? It’s because there’s so much money in them.

The concept is to have a qualified analyst buy a basket of goods (stock, or stocks and bonds) and manage them (buy and sell). And though it makes sense to spread risk over a basket of goods (as opposed to holding just a few investments), these companies charge a lot for their service. Typically 2.5% per year.

A portion of the fee—usually 1%—is paid to the adviser firm. It compensates them for dealing with the client and generally gets split 60/40 between firm and adviser. This leaves 1.5% for the fund company. So on a $6B fund that equates to $90M per year. Sure they have expenses, but at the most they hold 30-40 listings and employ 10 people. (Plus, sometimes they just buy the index or subcontract the whole thing out.)

And because management fees go on forever, they reduce your annual return. So if your fund makes 9%, you only see 6.5—that’s why most don’t beat the index. They also operate within a mandate. For example, if it’s a Canadian fund and Canada’s not the place to be, they can’t react. And they’re often forced to generate cash to pay out withdrawals and fees, so they sometimes sell when they don’t want to.

Bottom line: mutuals don’t operate in the environment customers like to imagine.

ETFs

To combat these big bucks, the world has invented a lower cost alternative—exchange-traded funds (ETFs). They use a computer generated model to buy and sell according to an index. And for this service, they charge between .25 and .95%. This way, customers get the low risk broad basket approach without being raped.

ETFs are certainly gaining in popularity but not because of advisers. Why? Because advisers don’t get paid the same. With EFTs, they earn like selling a stock—a one-time commission of around 2%. Not the 1% annual fee that goes with a fund.

Of course, the downside is no person has their hands on the levers. You’re totally relying on a software program. So if computers ever take over the world, you’ll probably lose all your money. To see a list of Canadian ETFs along with their Management Expense Ratio (MER), click here.

The market is dirty

Mature investors are aware the market is unethical in a number of ways.

Agencies, like Moody’s and Standard and Poor’s, rate organizations like GM on their ability to repay loans (corporate bonds). The higher the rating, the lower the interest. But they also get paid by GM. So how diligent are they when it comes to rating customers? And can you imagine how demanding companies like General Motors can be when it comes to paying out millions in interest—no wonder there are hookers on Wall Street. It’s a total conflict of interest.

This element caused most of the economic crisis of 2008. Agencies like Moody’s rated bundles of mortgage backed securities (CDOs) as triple A quality when in fact they contained loads of crap. So buyers (like, pension funds and municipalities) got screwed by trusting the ratings.

Another way the system is rigged started when brokerage houses merged with investment banks. In the olden days, investment banks took companies public and brokerage houses bought and sold stocks. The system worked well, but now investment firms do both. They take companies public and recommend the same stocks to their brokerage accounts (people like us). So not only is it a conflict of interest (because they’re paid at both ends), it messes with the buy, sell, hold recommendations.

If they rate a company poorly, what’s the chance of them getting the investment banking business in the future (e.g., when the customer wants to sell additional shares)? That’s why recommendations are either buy or hold—they can’t say sell.

Summary

Investors have to change with the circumstances. When you had little for savings it was easy to say, “I don’t have time for money.” But now that your little pot has grown, who doesn’t have time to make an extra $70K per year?

The crash of 2008 caused interest rates to plummet, which incented investors to move safer money into the market. This caused overvaluation—so we all made profit. But now that rates are starting to climb, that money may move back. And if it does, don’t get caught napping.

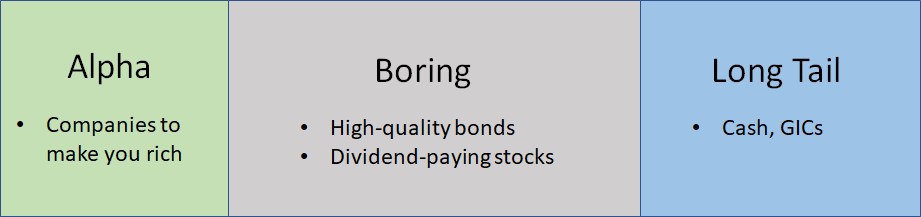

Managing money takes time and effort, even when you pay someone else to do it. And if this all seems too scary, maybe go with 5-year GICs—the results aren’t much different. Either way, half your investments should be in safe places and you should always have time for money.